This tutorial explains how to share a Git repository among developers.

It is meant for small teams who are adopting Git for the first time, and

want to get started quickly with a familiar setup before exploring Git's

many new possibilities.

If you follow this route, you will end up with a single centrally-hosted

repository that everyone in your group can use to publish their own work

and fetch whatever others have published. People used to a centralised

VCS will find this model easy to adjust to, but of course, each user's

"working copy" will itself be a fully-fledged Git repository, and many

new workflows are available to users as they learn more.

It would help if you're familiar with basic Git terminology and usage,

but if not, you can skim through to find out which commands you need to

read about and experiment with. (I recommend

Git from the bottom up

and the

Git tutorial

for an introduction.) I shall assume that everyone has git 1.6.5 or

later installed, and that they have ssh access to the server that will

host the repository.

Repository setup

In the ideal case, you create a repository on the server, clone it on

each workstation, and are ready to start work. That happy situation is

described below, as well as the all-too-likely addition of an existing

repository into the picture.

On the server

Use git init to create a new repository. The easy way to

give people read-write access to it is to add all the relevant users to

one group (say dev), and give that group ownership of the

repository:

$ git init --bare --shared foo.git

Initialized empty shared Git repository in /git/foo.git/

$ chgrp -R dev foo.git

It doesn't matter what user you run this command as. The

--shared option sets the permissions on everything in the

repository to group-writable.

Let's say the server is named example.org, and the new

repository lives in the /git/foo.git directory. To anyone

with ssh access to the server, the repository is now available at

ssh://example.org/git/foo.git.

Importing an existing repository

This can be done in many ways. My advice is to set up the new repository

on the server, push everything from the old repository into it, and

forget about the old repository.

$ cd existing.git

$ git push ssh://example.org/git/foo.git '*:*'

Counting objects: 3, done.

Writing objects: 100% (3/3), 204 bytes, done.

Total 3 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

Unpacking objects: 100% (3/3), done.

To ssh://example.org/git/foo.git

* [new branch] master -> master

The output above is from a test repository with a single commit. The

*:* notation pushes everything, including tags and remote

branches. If that's not what you want, use a more specific notation and

multiple pushes; or just get rid of any branches, remotes, or tags you

don't want before you push everything. There are many complications

possible at this step, but discussing them is not within the scope of

this article.

(Why forget about the old repository? It's just simpler that way, but if

you really want, you can configure it to pretend that it's just another

clone of the new repository.)

On the clients

Each user can now create their own copy of the central repository:

$ git clone ssh://example.org/git/foo.git

Initialized empty Git repository in /home/ams/foo/.git/

This clone is now configured to track the central repository,

which means that git pull will pull any commits from it

that you don't have already, and git push will push any

new commits back to it. The next sections explain how this works.

(Note: You'll see a warning about having cloned an empty repository if

you didn't push anything into foo.git. There's no problem

with starting from scratch, but you need to remember that the very first

push back to the central repository is special. More about that later.)

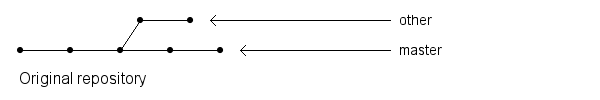

Let's pretend the original repository looks like the following diagram.

The dots are commits, and there are two branches named

master and other:

Pushing and pulling

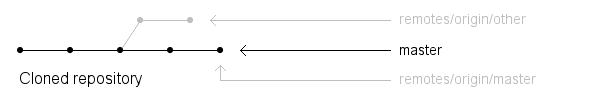

The newly-cloned repositories can refer to the central repository as

"origin", which is just a handy alias for the full ssh://

URL. During the initial cloning operation, any branches that exist in

the origin repository are saved as "remote branches" in the clone. A

branch named x in origin would be named

remotes/origin/x on the clone. Remote branches are meant to

represent the state of a remote repository, so you shouldn't commit to

them directly.

Instead, you should create a local branch that follows or tracks any

remote branch you're interested in; and this is done automatically for

the default branch, conventionally named master. After the

clone, you will have a remote branch named

remotes/origin/master, and a local branch named

master, which is checked out already. The former represents

the latest commit in origin. The latter follows along, but will include

your own local commits too.

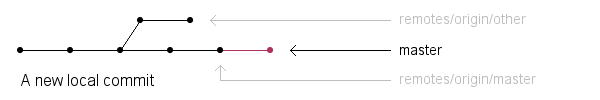

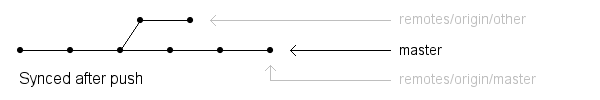

When you git commit, your master branch is

updated to point to the new commit. When you git push, your

master is used to update origin's master.

When you git pull, origin's master is used

to update your remotes/origin/master branch, which in turn

is used to update your own master branch.

Other people's changes

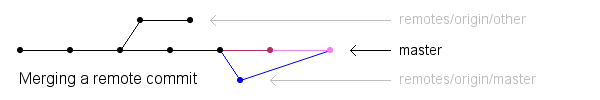

When multiple people push commits to a shared origin, the update process

involves an extra step. Suppose you push a commit while a colleague

creates a new local commit of her own. When she tries to git

push, the server rejects the push so as to not lose your commit

(which she doesn't have). She must then run git pull, which

will first update her origin/master remote branch to

include your commit, then merge it into her master so that

it includes both her commit and yours.

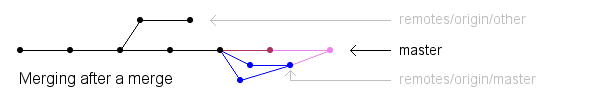

Her next git push will push the merged branch to origin. If

you run git pull next, your origin/master will

be updated to match origin's new master, then merged

into your master so that you have your colleague's commit

too, besides any new ones of your own. If you run git pull

without making any local changes, Git will update the remote-tracking

branch, and fast-forward your local branch to the new commit

without creating a new merge commit to record the event.

Merging and conflicts

If the various commits do not conflict, Git will merge them with no

intervention. Otherwise, it will merge any non-conflicting changes

automatically and ask you to resolve the remaining conflicts by hand.

Run git status to see which files have been merged, and

which ones need your attention. Look for ====== conflict

markers in each unmerged file, edit the surrounding text to fix the

problem, and run git add filename to mark that file

as resolved. When you're done, run git commit to complete

the merge. See

git-merge(1)

for more details.

Using other branches

You can create new local branches with git branch

branchname and switch between branches with git

checkout branchname. To push a new branch to the server,

run git push origin branchname. This will create a

branch named branchname in origin, and

remotes/origin/branchname in your repository. Anyone who

then runs git pull will get their own pair of

remote-tracking and local branches of that name.

If you do not explicitly push your new local branches, they stay in your

repository and are invisible to others. git push by default

pushes only those branches that already exist on the server. This is why

you have to explicitly git push origin master the first

time you push to an empty central repository. In contrast, git

pull will create local copies of any new branches on the server.

You can also use git remote to add nicknames for other

repositories than origin. You'll get a new set of remote-tracking

branches for the new remote repository, and you will have to specify the

name as an argument to git push and git pull,

but the transfer of commits will otherwise work in exactly the same way.

Pulling and pushing can be much more flexible than described

here—you can specify what branches to track and update

automatically, have different local names for branches, and so on. See

git-push(1)

and

git-pull(1)

for more.

Outgrowing this setup

Git offers many other workflow and configuration possibilities. Here are

a few directions to explore.

Use hooks

to automate tasks like sending email to the developers for every commit

or enforcing coding standards.

There are

graphical

frontends like git-cola and

QGit, and

repository

browsers like gitk and Gitweb (both distributed with Git). Use them

to browse history and assign blame.

Use git-bisect

to find out which commit broke a particular test case.

You may eventually need to provide read-only repository access to people

outside your own team/network—set up

git-daemon.

To give someone write access, just give them an ssh account on the

server; or install

gitolite

(the better-documented and better-maintained alternative to gitosis) for

fine-grained access control and easier user management.

With more users, the "everything in the master branch" model described

here may prove inadequate. There are many workflows that take

advantage of Git's easy branching and merging, such as

this nicely-illustrated one and

the suggestions in

gitworkflows(7).

Even if you adopt a more decentralised approach, you can keep using your

formerly-central repository as a fixed point of contact and for backups.

Questions are welcome

Questions are welcome, no matter how basic they are. By asking them, you

may help to improve this tutorial, and thus help future readers.

Thanks to everyone who commented on this document.