I have now lost count of the number of forwarded copies of the

“A scientist found a bird that hadn’t been seen in half a century, then killed it”

mail that people have sent me. The collection of a Bougainville

Moustached Kingfisher specimen by an AMNH team in Guadalcanal has

drawn intense criticism and reignited the debate about whether

scientific collection is justified or even necessary.

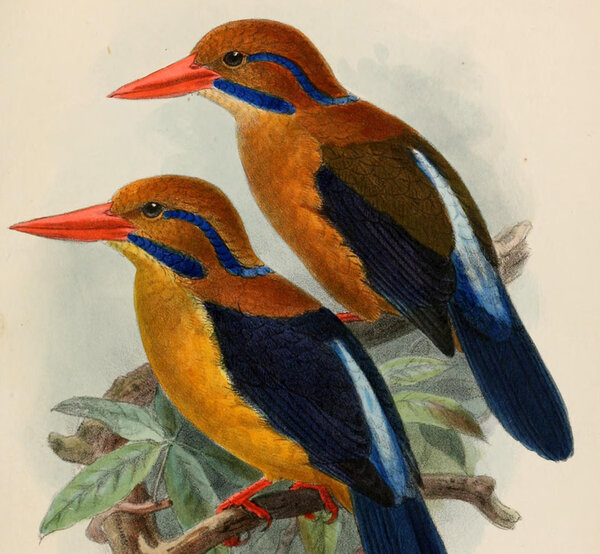

[Illustration: J G Keulemans (1842–1912),

Novitates Zoologicae]

[Illustration: J G Keulemans (1842–1912),

Novitates Zoologicae]

I don't have anything new or insightful to add to this debate.

As a bird-watcher, of course I prefer live birds to dead ones, so I

appreciate and can relate to the passion with which many have argued

that we should, above all, do no harm, and that we should be working

harder than ever to keep them alive.

As a realist, I must admit that most of what I know about live birds

comes in one way or another from dead ones (and the people who killed

them), perhaps especially from ones that died long before the ethics of

collecting specimens were debated at all.

I am not a conservationist or a biologist, and I have to live with this

uneasy equilibrium, lacking enough perspective to pick one side and

stick with it, and certainly not knowing enough about any specific

incident to either condemn or condone it.

I do know a thing or two about data, however, and I've heard suggestions

that we can take some definitive set of measurements from a live bird in

lieu of a specimen—or that we should at least be working to develop such

an ability—and that once we have it, we won't need specimens any more.

I think we're far from being able to take a complete “snapshot” of a

bird good enough to consider as a primary source of data about a new

species, but of course we can improve the nature and quantity of

information that can be collected from live birds without causing much

distress, and I'm sure that would be good news for everyone.

For any given research topic, one could imagine a set of observations

that would answer the question without a specimen. For example, the

oft-cited research that established a link between DDT and a thinning of

egg shells in various raptors could have been done if the eggs had been

measured and their thickness recorded at various points in some

non-destructive manner.

But at any given time, there will always be some measurements we can't

take and questions we can't imagine. In representing a live bird as

data, we will always be limited by the current state of the art. Unless

we never ask new questions or improve our instruments of measurement, we

will always lose something in the summarisation. (Some information is

lost even in the current specimen preservation process. I don't think

we're in a position to research, say, trends in the heart size of

raptors over time.)

We can choose to forego the preservation of a type specimen,

and perhaps in future our snapshots will improve to a point where this

decision becomes easier, but it will always involve a compromise one way

or another.

(Please ignore this link if you don't know what git is)

Aside: This dichotomy reminds me of a fundamental design

principle in Git, which differs from most other version control systems

in storing a complete tree of files for every commit, rather than a

summary of the differences from the previous commit. This decision

enabled features like rename detection across merges to be improved

progressively without changing the data format, because the detection is

always done using state-of-the-art code against the complete, canonical

data, rather than relying on decisions taken by older code with less

context available.