This article is about how pipes are implemented the Unix kernel. I was a

little disappointed that a recent article titled

“How do Unix pipes work?”

was not about the internals, and curious enough to go

digging in some old sources to try to answer the question.

What are we talking about?

Pipes are “perhaps the single most striking invention in

Unix” — a defining characteristic of the Unix philosophy of

composing small programs together, and a familiar sight in the Unix

shell:

$ echo hello | wc -c

6

This functionality depends on the kernel providing a system call named

pipe, which is described by the

pipe(7)

and

pipe(2)

manual pages:

Pipes provide a unidirectional interprocess communication channel. A

pipe has a read end and a write end. Data written to the write end of a

pipe can be read from the read end of the pipe.

A pipe is created using pipe(2), which returns two file descriptors, one

referring to the read end of the pipe, the other referring to the write

end.

Tracing the execution of the command above shows the creation of the

pipe and the flow of data through it from one process to another:

$ strace -qf -e execve,pipe,dup2,read,write \

sh -c 'echo hello | wc -c'

execve("/bin/sh", ["sh", "-c", "echo hello | wc -c"], …)

pipe([3, 4]) = 0

[pid 2604795] dup2(4, 1) = 1

[pid 2604795] write(1, "hello\n", 6) = 6

[pid 2604796] dup2(3, 0) = 0

[pid 2604796] execve("/usr/bin/wc", ["wc", "-c"], …)

[pid 2604796] read(0, "hello\n", 16384) = 6

[pid 2604796] write(1, "6\n", 2) = 2

The parent process calls pipe() to obtain connected fds, one child

writes to one fd and another reads the same data from the other fd. (The

shell uses dup2 to "rename" fds 3 and 4 to match stdin and stdout.)

Without pipes, the shell would have to write the output from one process

to a file and arrange for the next process to read from it, at the

expense of some overhead and some disk space — but pipes

provide more than just the convenience of avoiding temporary files:

If a process attempts to read from an empty pipe, then read(2) will

block until data is available. If a process attempts to write to a full

pipe (see below), then write(2) blocks until sufficient data has been

read from the pipe to allow the write to complete.

This important property, along with the POSIX requirement that writing

up to PIPE_BUF (at least 512) bytes into a pipe must be atomic, allows

processes to communicate with each other over a pipe in a way that

regular files (which have no such guarantees) could not support.

With a regular file, a process could write all its output and hand it

over to the next process, or they could operate in lock-step by using an

external signalling mechanism (like a semaphore) to let each other know

when they were done reading or writing. Pipes eliminate all this

complexity.

What are we looking for?

A little hand-waving helps to imagine how pipes might work. You would

need to allocate a memory buffer and some state, have functions to add

and remove data from the buffer and some glue to invoke them through

read and write operations on file descriptors, and sprinkle some locking

on top to implement the special behaviour described above.

We are now equipped to interrogate the kernel source under bright lights

to confirm or deny this vague mental model, but always prepared to run

into any surprises along the way.

Where do we look?

I'm not sure where my (reprinted) copy of the famous

“Lions book”

with the source code of Unix 6ed is, but thanks to

The Unix Heritage Society,

we can start by looking at even older

Unix sources

online.

(Browsing the TUHS archives is like being in a museum — not

only does it provide a rare glimpse at our shared history, it also makes

me appreciate the years of effort that went into recovering all of these

materials bit by bit from old tapes and printed documentation, and

acutely conscious of the parts that are still lost.)

Once we've satisfied our curiosity about the ancient history of pipes,

we can take a look at some modern kernels just for the contrast.

Incidentally, pipe is system call number 42 in the sysent[] table in

Unix. Coincidence?

I can't find any trace of pipe(2) in

PDP-7 Unix

from January 1970, nor in

First edition Unix

from November 1971, nor in the incomplete sources of

Second edition Unix

from June 1972.

TUHS confirms that

Third edition Unix

from February 1973 was the first version to include pipes:

The third edition of Unix was the last version with a kernel still

written in assembly code, but is the first version to include pipes. For

much of 1973, the existing Third Edition was maintained and improved,

while the kernel was rewritten in C to become the Fourth Edition of

Unix.

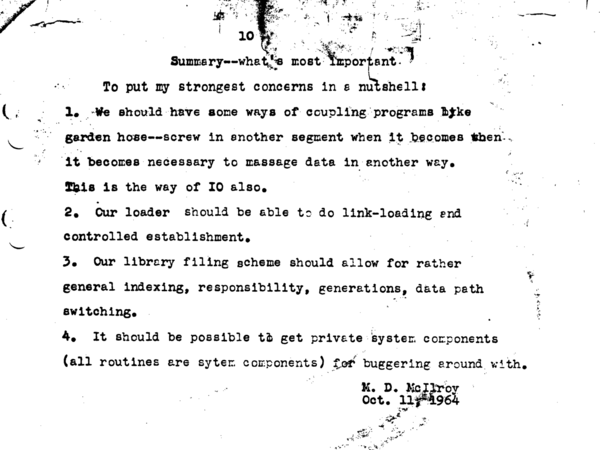

Update: A reader on HN was kind enough to dig up a scanned copy

of the 1964 memo in which Doug McIlroy proposed the idea of “coupling

programs like garden hose”.

Brian Kernighan's book,

“Unix: A History and a Memoir”,

also talks about the history of pipes and mentions this memo “…that hung

on the wall in my office at Bell Labs for 30 years”. Here's an

interview with McIlroy,

and some more history from a

2014 paper by McIlroy:

When Unix came to be, my fascination with coroutines led me to badger its author, Ken Thompson, to allow writes in one process to go not only to devices but also to matching reads in another process. Ken saw that was possible. As a minimalist, though, he wanted every system feature to carry significant weight. Did direct writes between processes offer a really major advantage over writing to a temporary file in one process and then reading it in the other? Not until I made a specific proposal with a catchyname, ‘‘pipe’’, and shell syntax to connect processes via pipes, did Ken finally exclaim, ‘‘I’ll do it!’’

And he did do it. In one feverish evening Ken modified both kernel and shell, and fixed several standard programs so they could take input from standard input (potentially piped) as well as named files. The next day brought a heady explosion of applications. By the end of the week, department secretaries were using pipes to send text-processor output to the printer spooler. Not long after, Ken replaced the original API and shell syntax for pipes with cleaner conventions that have been used ever since.

Unfortunately, the source code for the 3E kernel is no longer available,

and although we do have the C source code for a version of the

Fourth edition Unix

kernel from November 1973, it predates the official release by a few

months, and is missing the pipe implementation. It is sad that the

origin of such an iconic Unix feature is lost to us, perhaps forever.

We do have the pipe(2) manpages from both releases, so we can start by

looking at the documentation from

3E

(with certain words underlined “by hand” with a string of literal ^H

backspaces followed by underscores!). This proto-pipe(2) written in

assembly returned only one file descriptor, but provided the basic

functionality that we expect:

The pipe system call creates an I/O mechanism called a pipe. The

file descriptor returned can be used in both read and write operations.

When the pipe is written, the data is buffered up to 504 bytes at which

time the writing process is suspended. A read on the pipe will pick up

the buffered data.

By next year, along with a rewrite of the kernel into C, the

4E pipe(2)

had assumed its modern form, with a prototype of "pipe(fildes)":

The pipe system call creates an I/O mechanism called a pipe. The

file descriptors returned can be used in read and write operations. When

the pipe is written using the descriptor returned in r1 (resp.

fildes[1]), up to 4096 bytes of data are buffered before the writing

process is suspended. A read using the descriptor returned in r0 (resp.

fildes[0]) will pick up the data.

It is assumed that after the pipe has been set up, two (or more)

cooperating processes (created by subsequent fork calls) will

pass data through the pipe with read and write calls.

The shell has a syntax to set up a linear array of processes connected

by pipes.

Read calls on an empty pipe (no buffered data) with only one end (all

write file descriptors closed) return an end-of-file. Write calls under

similar conditions are ignored.

So the earliest

surviving pipe implementation

is from

Fifth Edition Unix

in June 1974, but it's nearly identical to what was in the next release,

which also added some comments, so we might as well skip 5E too.

As so many others have done in the past,

Sixth Edition Unix

from May 1975 is where we start reading the Unix code. Sixth Edition

sources are much more widely available than earlier versions, thanks

largely to the Lions book:

For many years, the Lions book was the only Unix kernel documentation

available outside Bell Labs. Although the license of 6th Edition allowed

classroom use of the source code, the license of 7th Edition

specifically excluded such use, so the book spread through illegal copy

machine reproductions.

You can still buy a reprint of the book, featuring cover art with

shifty-looking students at a photocopier, but thanks to Warren Toomey

(who went on to start TUHS), you can also download

a PDF of the 6E source.

I can't resist a quick glimpse at the effort that went into making this

PDF available:

Over 15 years ago I had produced a replica of the Lions' source code

listing since I was unhappy with the quality of my n-th generation copy.

There was no TUHS and I had no access to any old source code. But in

1988 I discovered an old 9-track tape being discarded of a PDP11 backup.

It was hard to determine what it was running, but it did have an intact

/usr/src/ tree of which most of the files were timesamped 1979, even at

that time it seemed ancient. So it was either 7th edition or a

derivative like PWB, which I believe it was.

I used this as a basis and hand edited the source back into 6th edition

form. Some code was completely the same, some required the easy edit of

changing the modern += token into the archaic =+. Others needed to just

remove casts, while some had to be completely retyped, but not that

much.

Now, decades later, we can just read the Sixth Edition source code

online at TUHS, from an archive

contributed by Dennis Ritchie.

Aside: at first glance, what is most striking about this pre-K&R C code

is how narrow it is. It's not often that I can include code

listings without extensive editing to fit the relatively narrow body

of my web site.

There's an instructive comment near the top of

/usr/sys/ken/pipe.c

(and yes, there's also a

/usr/sys/dmr):

/*

* Max allowable buffering per pipe.

* This is also the max size of the

* file created to implement the pipe.

* If this size is bigger than 4096,

* pipes will be implemented in LARG

* files, which is probably not good.

*/

#define PIPSIZ 4096

The buffer size has not changed from 4E days, but here we can already

see beyond the documented public interface — ancient pipes

used a file to provide the backing storage!

As for LARG files, they correspond to

the ILARG inode flag

used by the "large addressing algorithm" to handle

indirect blocks

to support larger filesystems. If Ken says it would probably not be good

to use them, I'm happy to take his word for it.

Here's the actual pipe system call:

/*

* The sys-pipe entry.

* Allocate an inode on the root device.

* Allocate 2 file structures.

* Put it all together with flags.

*/

pipe()

{

register *ip, *rf, *wf;

int r;

ip = ialloc(rootdev);

if(ip == NULL)

return;

rf = falloc();

if(rf == NULL) {

iput(ip);

return;

}

r = u.u_ar0[R0];

wf = falloc();

if(wf == NULL) {

rf->f_count = 0;

u.u_ofile[r] = NULL;

iput(ip);

return;

}

u.u_ar0[R1] = u.u_ar0[R0]; /* wf's fd */

u.u_ar0[R0] = r; /* rf's fd */

wf->f_flag = FWRITE|FPIPE;

wf->f_inode = ip;

rf->f_flag = FREAD|FPIPE;

rf->f_inode = ip;

ip->i_count = 2;

ip->i_flag = IACC|IUPD;

ip->i_mode = IALLOC;

}

The comment is quite clear about what's going on, but the code takes a

bit of effort to follow, partly because of how the system call

parameters and return values are passed in and out through the

per-process

“struct user u”

and the registers R0 and R1.

We try to allocate

an inode

on disk

using ialloc()

and two

files

in memory

using falloc().

If all goes well, we set flags to identify the files as two ends of a

pipe, point them at the same inode (whose reference count becomes 2),

and mark the inode as modified and in-use. (Note the

calls to iput()

in the error paths, to decrement the reference count of the new inode.)

pipe() must return the read and write file descriptor numbers via R0/R1.

falloc() returns a pointer to a file structure, but also "returns" the

fd via u.u_ar0[R0]. So the code saves the read fd in r and assigns the

write fd directly from u.u_ar0[R0] after the second call to falloc().

The FPIPE flag that we set during pipe creation controls the behaviour

of the

rdwr() function in sys2.c,

which invokes the custom pipe I/O routines for pipes:

/*

* common code for read and write calls:

* check permissions, set base, count, and offset,

* and switch out to readi, writei, or pipe code.

*/

rdwr(mode)

{

register *fp, m;

m = mode;

fp = getf(u.u_ar0[R0]);

/* … */

if(fp->f_flag&FPIPE) {

if(m==FREAD)

readp(fp); else

writep(fp);

}

/* … */

}

Next in pipe.c is the readp() function to read from a pipe, but it's

easier to follow the implementation by looking at writep() first. Once

again, the oddities of the argument passing convention add some

complexity, but we can gloss over some of the details.

writep(fp)

{

register *rp, *ip, c;

rp = fp;

ip = rp->f_inode;

c = u.u_count;

loop:

/* If all done, return. */

plock(ip);

if(c == 0) {

prele(ip);

u.u_count = 0;

return;

}

/*

* If there are not both read and write sides of the

* pipe active, return error and signal too.

*/

if(ip->i_count < 2) {

prele(ip);

u.u_error = EPIPE;

psignal(u.u_procp, SIGPIPE);

return;

}

/*

* If the pipe is full, wait for reads to deplete

* and truncate it.

*/

if(ip->i_size1 == PIPSIZ) {

ip->i_mode =| IWRITE;

prele(ip);

sleep(ip+1, PPIPE);

goto loop;

}

/* Write what is possible and loop back. */

u.u_offset[0] = 0;

u.u_offset[1] = ip->i_size1;

u.u_count = min(c, PIPSIZ-u.u_offset[1]);

c =- u.u_count;

writei(ip);

prele(ip);

if(ip->i_mode&IREAD) {

ip->i_mode =& ~IREAD;

wakeup(ip+2);

}

goto loop;

}

On entry, we want to write u.u_count bytes into the pipe. First we

acquire a lock on the inode (see below for more about plock/prele).

Next, we check the inode's reference count. So long as the two ends of

the pipe remain open, the reference count must remain 2. We hold one

reference (from rp->f_inode), so if the count is less than 2, it must

mean that the reader closed their end. In other words, we're trying to

write into a closed pipe, which is an error. 6E Unix is when the EPIPE

error code and SIGPIPE signal were first introduced.

Even if the pipe is still open, it may be full. In that case, we release

the lock and go to sleep hoping that another process will create space

in the pipe by reading from it. When we are woken up, we loop back to

the start and try to acquire the lock and start another write cycle.

If the pipe does have free space, we use

writei()

to write out some data. The inode's i_size1 (which may be 0 for an empty

pipe) points to the end of whatever data it already contains. If we have

enough data to write, we can fill the pipe from i_size1 up to PIPESIZ.

Then we release the lock and try to wake up any process that is waiting

to read from the pipe. Finally, we loop back to the start to see if we

managed to write out as many bytes as we wanted. If not, we start

another write cycle.

The inode's i_mode is normally used to hold r/w/x permissions, but for

pipes the IREAD and IWRITE bits are used to indicate that some process

is waiting to read from or write to the pipe, respectively. The process

sets the flag and calls sleep(), expecting a matching wakeup() to be

called by some other process in future.

The real magic happens in sleep() and wakeup(), which are implemented in

slp.c,

the source of the infamous “You are not expected to understand this”

comment. Fortunately, we don't have to understand the code, just take a

quick look at some other comments:

/*

* Give up the processor till a wakeup occurs

* on chan, at which time the process

* enters the scheduling queue at priority pri.

* The most important effect of pri is that when

* pri<0 a signal cannot disturb the sleep;

* if pri>=0 signals will be processed.

* Callers of this routine must be prepared for

* premature return, and check that the reason for

* sleeping has gone away.

*/

sleep(chan, pri) /* … */

/*

* Wake up all processes sleeping on chan.

*/

wakeup(chan) /* … */

A process that calls sleep() for a particular channel can be woken up

later by another process calling wakeup() for the same channel. writep()

and readp() coordinate their operations through matching pairs of these

calls. (Note that pipe.c always uses PPIPE as the priority when calling

sleep, so the sleeps are interruptible by signals.)

Now we have everything we need to understand the readp() function:

readp(fp)

int *fp;

{

register *rp, *ip;

rp = fp;

ip = rp->f_inode;

loop:

/* Very conservative locking. */

plock(ip);

/*

* If the head (read) has caught up with

* the tail (write), reset both to 0.

*/

if(rp->f_offset[1] == ip->i_size1) {

if(rp->f_offset[1] != 0) {

rp->f_offset[1] = 0;

ip->i_size1 = 0;

if(ip->i_mode&IWRITE) {

ip->i_mode =& ~IWRITE;

wakeup(ip+1);

}

}

/*

* If there are not both reader and

* writer active, return without

* satisfying read.

*/

prele(ip);

if(ip->i_count < 2)

return;

ip->i_mode =| IREAD;

sleep(ip+2, PPIPE);

goto loop;

}

/* Read and return */

u.u_offset[0] = 0;

u.u_offset[1] = rp->f_offset[1];

readi(ip);

rp->f_offset[1] = u.u_offset[1];

prele(ip);

}

It may help to read this function from the bottom upwards. The "read and

return" branch is the common case, when there is some data in the pipe.

If so, we use

readi()

to read as much data as available from the current read f_offset

onwards, and update the offset accordingly.

On a subsequent read, the pipe is empty if the read offset has reached

the inode's i_size1. We reset the positions to 0 and try to wake up any

process that wants to write into the pipe. We know that writep() goes to

sleep on on ip+1 when the pipe is full. Now that the pipe is empty, we

can wake it up and allow it to resume its write loop.

If there's nothing to read, readp() can set the IREAD flag and go to

sleep on ip+2. We know that writep() will wake it up when it manages to

write some data into the pipe.

It's worth a quick look at the comments for

readi() and writei()

to realise that, other than having to pass in the parameters through

“u”, we can treat them as ordinary IO functions that take a file, a

position, a memory buffer, and a count of bytes to read or write.

/*

* Read the file corresponding to

* the inode pointed at by the argument.

* The actual read arguments are found

* in the variables:

* u_base core address for destination

* u_offset byte offset in file

* u_count number of bytes to read

* u_segflg read to kernel/user

*/

readi(aip)

struct inode *aip;

/* … */

/*

* Write the file corresponding to

* the inode pointed at by the argument.

* The actual write arguments are found

* in the variables:

* u_base core address for source

* u_offset byte offset in file

* u_count number of bytes to write

* u_segflg write to kernel/user

*/

writei(aip)

struct inode *aip;

/* … */

As for the "conservative" locking, readp() and writep() hold a lock on

the inode until they finish or yield (i.e., call wakeup). plock() and

prele() are straightforward, with another matched set of sleep and

wakeup calls to enable us to wakeup any process that wants a lock that

we have just released:

/*

* Lock a pipe.

* If its already locked, set the WANT bit and sleep.

*/

plock(ip)

int *ip;

{

register *rp;

rp = ip;

while(rp->i_flag&ILOCK) {

rp->i_flag =| IWANT;

sleep(rp, PPIPE);

}

rp->i_flag =| ILOCK;

}

/*

* Unlock a pipe.

* If WANT bit is on, wakeup.

* This routine is also used to unlock inodes in general.

*/

prele(ip)

int *ip;

{

register *rp;

rp = ip;

rp->i_flag =& ~ILOCK;

if(rp->i_flag&IWANT) {

rp->i_flag =& ~IWANT;

wakeup(rp);

}

}

I could not understand at first why readp() did not call prele(ip)

before calling wakeup(ip+1). The first thing writep() does in its loop

is plock(ip), which would deadlock if readp() still held its lock, so

the code must have the right effect somehow. A quick glance at wakeup()

showed that it only marks sleeping processes as runnable, and leaves it

to a future sched() to actually start the process. So readp() calls

wakeup(), releases its lock, sets IREAD, and calls sleep(ip+2) all

before writep() resumes its loop.

That's all there is to pipes in 6E. Simple code, far-reaching

consequences.

Seventh Edition Unix

from January 1979 was a major new release (after a gap of four years)

with many new applications and kernel features. It also featured

widespread changes due to the use of K&R C with typecasts and unions and

typed pointers to structs, but the

pipe code

hardly changed at all. We can skip it without missing anything exciting.

Xv6 is a

kernel inspired by Sixth Edition Unix, but written in modern C to run on

x86 processors. It's simple to read and understand but, unlike the Unix

sources from TUHS, you can also compile and modify and run it on

something other than a PDP 11/70. For this reason, it is widely used by

universities in Operation Systems courses. The

source code is

available on Github.

It has a clear and concise

pipe.c implementation

backed by a buffer in memory instead of an inode on disk. I reproduce

only the definition of “struct pipe” and the pipealloc() function here:

#define PIPESIZE 512

struct pipe {

struct spinlock lock;

char data[PIPESIZE];

uint nread; // number of bytes read

uint nwrite; // number of bytes written

int readopen; // read fd is still open

int writeopen; // write fd is still open

};

int

pipealloc(struct file **f0, struct file **f1)

{

struct pipe *p;

p = 0;

*f0 = *f1 = 0;

if((*f0 = filealloc()) == 0 || (*f1 = filealloc()) == 0)

goto bad;

if((p = (struct pipe*)kalloc()) == 0)

goto bad;

p->readopen = 1;

p->writeopen = 1;

p->nwrite = 0;

p->nread = 0;

initlock(&p->lock, "pipe");

(*f0)->type = FD_PIPE;

(*f0)->readable = 1;

(*f0)->writable = 0;

(*f0)->pipe = p;

(*f1)->type = FD_PIPE;

(*f1)->readable = 0;

(*f1)->writable = 1;

(*f1)->pipe = p;

return 0;

bad:

if(p)

kfree((char*)p);

if(*f0)

fileclose(*f0);

if(*f1)

fileclose(*f1);

return -1;

}

pipealloc() sets the stage for the rest of the implementation,

comprising piperead(), pipewrite(), and pipeclose() functions. The

actual system call, sys_pipe, is a wrapper implemented in

sysfile.c.

I recommend reading the code in its entirety. It's about the same level

of complexity as the 6E Unix source code, but much easier to go through,

therefore more satisfying.

It's possible to find the

Linux 0.01 source code,

and it's instructive

to look at its pipe implementation in fs/pipe.c too. It uses an inode to

represent the pipe, but it's written in modern C. Having worked our way

through the 6E code, it's not difficult to follow. Here's the

write_pipe() function:

int write_pipe(struct m_inode * inode, char * buf, int count)

{

char * b=buf;

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

if (inode->i_count != 2) { /* no readers */

current->signal |= (1<<(SIGPIPE-1));

return -1;

}

while (count-->0) {

while (PIPE_FULL(*inode)) {

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

if (inode->i_count != 2) {

current->signal |= (1<<(SIGPIPE-1));

return b-buf;

}

sleep_on(&inode->i_wait);

}

((char *)inode->i_size)[PIPE_HEAD(*inode)] =

get_fs_byte(b++);

INC_PIPE( PIPE_HEAD(*inode) );

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

}

wake_up(&inode->i_wait);

return b-buf;

}

Even without looking up the structure definitions, we can understand the

use of the inode reference count to check if a write should raise

SIGPIPE. Other than operating byte-by-byte, it's easy to map this

function to the ideas we saw earlier. Even the sleep_on/wake_up logic

doesn't seem entirely foreign.

I had a quick look at some modern kernels, and none of them uses a

disk-backed implementation any more (not surprisingly). Linux has its

own implementation, of course, but although the three modern BSD kernels

all have implementations derived from code written by John S. Dyson,

they too have diverged from each other over the years.

Reading through fs/pipe.c (on Linux) or sys/kern/sys_pipe.c (on *BSD)

now takes real commitment. The code now needs to be concerned with

performance and support for features like vectored and asynchronous IO,

and the details of memory allocation, locking, and kernel configuration

all vary considerably. Not at all the sort of thing a university would

want for an introductory course.

Nevertheless, I took some satisfaction in being able to recognise a few

ancestral patterns (raising SIGPIPE and returning EPIPE when writing to

a closed pipe, for example) in each of these very different modern

kernels. I may never see a PDP-11 computer, but there are still useful

lessons to learn from code that predates my own existence by a few

years.

“The Linux Kernel Implementation of Pipes and FIFOs”

by Divye Kapoor in 2011 is an overview of how pipefs (still) works in

Linux. This

recent Linux commit

illustrates how pipes support a model of interaction that goes beyond

what temporary files allow, as well as how much further pipes have

evolved from the "very conservative locking" in the 6E Unix kernel.